Researchers from TU Wien and its polymer manufacturing spin-off Cubicure have developed an SLA 3D printable ivory substitute that can be used to restore damaged historical artefacts.

Once printed, the scientists’ ‘Digory’ material, composed of a synthetic resin embedded with calcium phosphate and silicon oxide, yields parts with a similar appearance and properties to real ivory. Utilizing the new polymer, the team have been able to repair a 17th century coffin, proving its potential as a less wasteful, time-consuming and more elephant-friendly way of renovating monuments.

“With our specially-developed 3D printing systems, we process different material formulations for completely different areas of application, but this project was also something new for us,” said Konstanze Seidler of Cubicure’s Material R&D division. “In any case, it’s further proof of how diverse the possible applications of SLA are.”

Identifying an ivory substitute

Often sourced from elephant tusks or the teeth of warthogs, walruses or hippopotamuses, ivory is highly sought after because it combines rigid durability with attractive aesthetics. However, due to the ethical concerns raised by poaching, international trading of the material has been banned since 1989, and this has left many damaged ivory artefacts without a means of repair.

While various substitutes have been made from polymers, casein or even ivory sawdust, they’re often produced in bulk, meaning that parts need to be carved-out in a resource-heavy process. 3D printing, meanwhile, is increasingly being used to restore cultural monuments, thus Addison Restoration reached out to Cubicure last year on behalf of the Archdiocese of Vienna, for help repairing a historical casket.

“The research project began with a valuable 17th century state casket in the parish church of Mauerbach,” said Professor Jürgen Stampfl, from the Institute of Materials Science and Technology at TU Wien. “It is decorated with small ivory ornaments, some of which have been lost over time. The question was whether they could be replaced with 3D printing technology.”

3D printing a column capital

In order to accurately replicate the casket’s appearance, the scientists formulated their new material, by loading a dimethacrylate resin with Tricalcium phosphate (TCP) particles, yielding a translucent slurry. The mixture was then topped-up with colored pigments, as part of a finely-balanced process that needed to be perfected, to produce parts with tones that exactly replicated the real artefact.

“You have to bear in mind that ivory is translucent,” explained Thaddäa Rath, a student who contributed to the project for her dissertation. “Only if you use the right amount of calcium phosphate, will the material have the same translucent properties as ivory.”

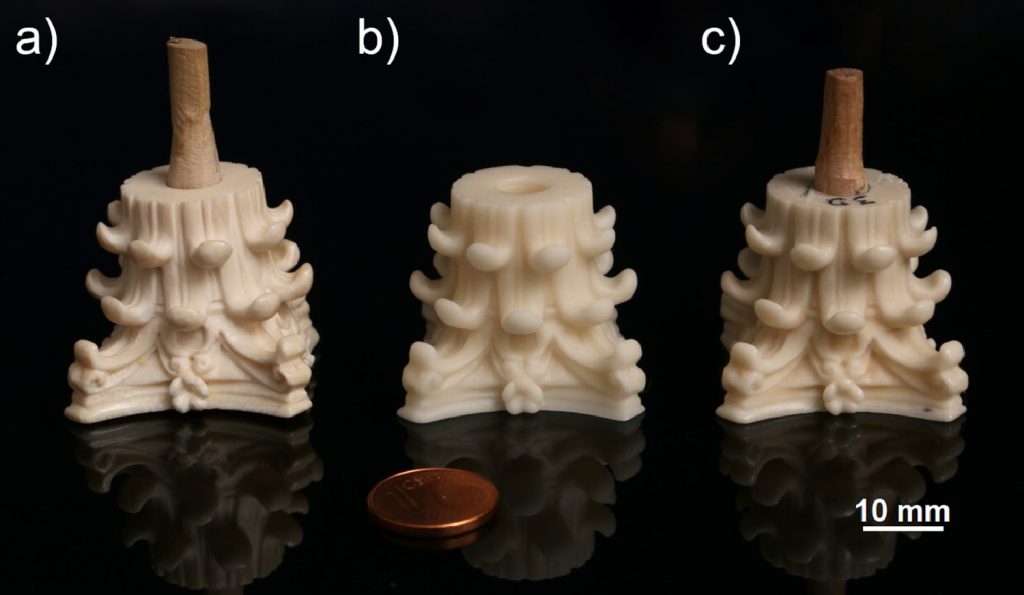

Once their Digory resin was ready, the researchers processed it using Cubicure’s Caligma 200 Hot Lithography 3D printer, creating two sample chess pawns, as well as a column capital for the 17th century tomb. After some manual sandpaper polishing, the scientists compared their samples to genuine ivory, finding that they had a comparable level of density and no crucial inhomogeneities.

The 3D printed replicas also exhibited a similar flexural modulus to ivory, including a flexural strength of 74% under bending. However, the team did concede that the color pigments hadn’t penetrated their replica very well, leading to some height and temperature differences compared to the original, and leaving the process needing some further tweaks before it can be scaled effectively.

In terms of dimensional accuracy and appearance though, the team were able to match the original casket’s columns exactly, even coloring them with black ink to replicate the cracks seen in the damaged articles. As a result, the scientists consider their approach to represent a “big step forward” in artefact restoration, making it much more economically-viable than existing manual techniques.

Preserving history with 3D printing

Utilizing a combination of 3D scanning and printing technologies, it’s now possible to recreate historic monuments with an exceptionally-high level of accuracy. Researchers from the Yungang Grottoes Research Institute, for instance, have 3D printed ancient Buddhist statue replicas for public display, to protect them from potential weathering.

A team based at London’s Imperial War Museum (IWM) have taken a similar approach, by using imagery to 3D print a 3000 year-old statue replica. The original monument, called the ‘Lion of Mosul,’ was destroyed by ISIS six years ago, but AM has allowed the researchers to recreate, preserve and display the cultural treasure at a public exhibition.

Similarly, the Dubai Future Foundation has worked as part of a UN-backed initiative for the last four years to 3D print rare artefacts that have been destroyed by ISIS across Iraq and Syria. Some of the foundation’s work has since been displayed in the “The Spirit in the Stone” exhibition at the UN’s headquarters in New York.

The researchers’ findings are detailed in their paper titled “Developing an ivory-like material for stereolithography-based additive manufacturing.” The research was co-authored by Thaddäa Rath, Otmar Martl, Bernhard Steyrer, Konstanze Seidler, Richard Addison, Elena Holzhausen and Jürgen Stampfl.

To stay up to date with the latest 3D printing news, don’t forget to subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter or follow us on Twitter or liking our page on Facebook.

Are you looking for a job in the additive manufacturing industry? Visit 3D Printing Jobs for a selection of roles in the industry.

Featured image shows the researchers’ 3D printed column capital replica alongside the genuine article. Photo via the Applied Materials Today journal.