Aurich Lawson / Getty Images

If you told any executive at a major corporation in mid-2019 that close to half of the US workforce would be working from home within the next year, they would have at least raised a skeptical eyebrow (and then probably called security to have you removed). Yet, here we are.

Major technology companies, including Microsoft, Facebook, and Google, have closed their physical offices until well into 2021. Twitter has told many employees that they can work from home permanently. And now that we have nearly six months of involuntary widespread work-from-home behind us, many other organizations are also reconsidering the value of office space.

In April, a Gallup poll showed 62 percent of the workforce working from home, and 59 percent hoping they could continue to do so as much as possible once the pandemic is under control. While the numbers have since dropped to some degree—Stanford Institute for Economic Research figures in June showed only 42 percent of the US workforce working from home full-time—the fact remains that people’s relationship with their workplace has been dramatically restructured, perhaps permanently.

Laurie Noble / Getty Images

Management seems to be coming to the same conclusions. An April Gartner survey found 74 percent of chief financial officers planning to at least partially fulfill that wish, moving some portion of their workforce to permanent remote work to cut costs. The question is to what degree companies will transform their definition of the office to take advantage of the cultural and technical adjustments they’ve made to keep things moving while offices are empty.

However long it takes to get to the point where we can put the COVID-19 pandemic behind us, it seems certain that the role of « the office » is bound to change. You don’t have to search very hard to find utopian stories about the « office of the future » and « work after COVID. »

This is not going to be one of them.

I have not come as a herald of the new, shiny, corporate workspace of the future—instead, I’d like to throw a bucket of cold reality on the hype fire. What the past six months have taught leadership at many organizations is that their businesses can function adequately without people in the office and that balance sheets would look a lot more attractive if they could get rid of some of those real estate expenses. Prepare for the onslaught of multi-year management consulting engagements.

I do not claim any psychic powers. But as someone who has worked in both « hybrid » and full-time work-at-home capacities for many, many years, I have some sense of what offices should be in the future—and what many of them inevitably will become.

What is the office for, anyway?

For a very long time, the office has been the factory floor of information work. It’s existed as a warehouse of raw materials (office supplies) and finished goods (filed reports, balance sheets, and presentations). It’s an assembly line of content, a stockyard for employees where managers can count heads in seats and monitor productivity. It is also the vessel of corporate culture, where employees are marinated for good or ill in the stew of management and mismanagement, team building and destroying, and the occasional conference room cluster.

As work has become increasingly digitized, the production line aspect of an office space has become less and less tethered to the physical space. But up until recently, that didn’t dramatically change the role of the physical office, particularly in industries that are not tech-centric or tech-adjacent. Part of the reason is that for most of its history IT infrastructure itself mirrored the factory metaphor of work, with work tightly coupled to internal IT resources and access to data dependent on connection to very specific networks. But this in-person mandate was also partially because face-to-face interactions were seen as essential to organizational cohesion and effective management.

Compassionate Eye Foundation / Karan Kapoor / Getty Images

Some organizations—like consulting firms—can function pretty well without an office, because they’ve traditionally been out of the office most of the time anyway. But for many organizations, the office provides some things that cannot be replicated with total fidelity in an all-remote environment—places such as the public library where my wife works. She’s already returned nearly full-time to the workplace, but there have been some obvious changes.

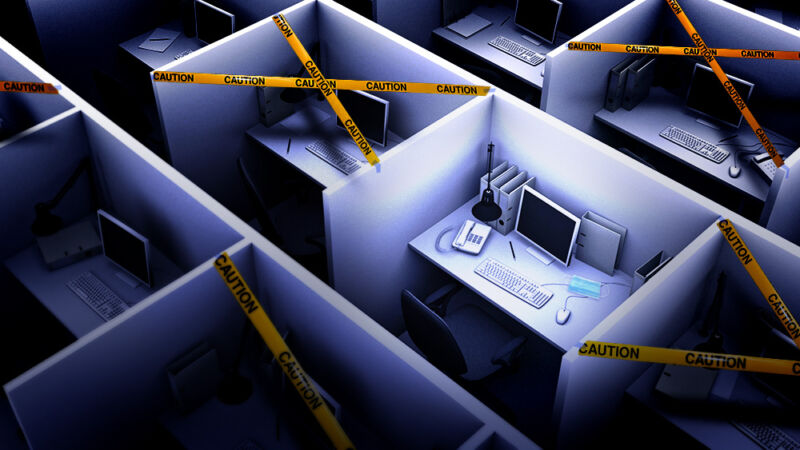

At first, only small shifts of staff were rotated into the library branches, before bringing people in for reduced-length days. Everyone socially distances and wears masks; the break room has an occupancy limit of one. Cabinets that used to hold coffee creamer, sugar, and other delights are now police-taped like a crime scene. Since there’s not enough space for social distancing in the staff workroom, tasks like program planning, coordinating meetings, scheduling, and professional development all are best executed remotely. Accordingly, everyone now has work-at-home hours on their schedule.

Even when a good deal of remote work is possible, there are certain things that are lost without having some time in the office. Mentoring, informal in-person collaboration, and other intangibles can suffer without a shared physical space. Technical support may not be totally adequate for peak productivity, either. And while not having to commute has allegedly helped with « work-life balance » during the lockdown, many people would be a lot happier if they could go to the office a few days a week to get better division of work and family life—yes, even if it’s just to go hide from their kids for a few hours in a co-working facility.