During our recent Cleantech Forum San Francisco in January, we coined 2020 as the Year of the SPAC in Cleantech. And it was clear that, for many CEOs and venture and growth capital investors, this is the top of mind topic right now.

And so it should be.

This new source of capital from SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, sometimes referred to as blank check companies) offers potential for private, growth-oriented companies in our space. They can:

- Fully fund their roll-out plans for the first half of the 2020s.

- Pick up a higher valuation.

- Provide good returns to their venture backers whose funds typically do not have the depth to take them through scale-up.

In my humble opinion, you cannot afford to be neutral on this trend, be you a CEO or a board member, even if you end up concluding it is not a route you wish to take for whatever reason, be that for now or forever. What happens to your company’s future potential if, for example, your chief rival does go this route and ends up with $0.5 billion of cash on hand?

In the spirit of our mission to provide access to the trends, companies and people shaping the future, this is a trend we will revisit regularly in 2021, certainly each quarter. It’s going to be a ride.

Today I will provide a baseline, bringing facts and figures to how the SPAC in cleantech emerged in 2020, especially the second half, as the new phenomenon in cleantech, in North America particularly but with wider ramifications. And I will look at how 2021 has begun for clues as to the likely direction of travel this year.

Key numbers on SPACs in 2020 for context: why does it matter?

IPO capital raised in the US via SPACs outpaced traditional listings in 2020, according to Goldman Sachs.

There were 248 SPAC IPO’s in 2020 (vs 225 for the whole of the prior decade). They raised $83 billion, averaging $335 million each, according to SPACInsider.com. To give that last number some context, Beyond Meat, the highest profile IPO in 2019 from our cleantech innovation theme, raised about $240 million in their traditional IPO.

What kind of acquisition targets is this new wave of SPACs landing on?

In the search phase, it can be hard to know from the outside where any individual SPAC might go. Researching each one can help for sure, as they all give some form of statement on possible targets. But many are quite general and have deliberately given themselves lots of flexibility. An example of how broad some descriptions are:

“While the Company may pursue an initial business combination with any target business and in any sector or geographical location, it intends to focus its search on companies operating in the technology, media, telecommunications and fintech sectors that are headquartered in Europe, Israel, the Middle East or North America”

Some are much more obviously going to be in scope for cleantech, be it via the name (e.g. ECP Environmental Growth Opportunities Corp), the background of the sponsors or the description in the SEC filings.

But the best data lies for now in the targets already announced as definitive agreements, and the completions of the reverse merger IPO’s.

In this regard:

- 47 SPACS completed their IPOs in 2019 and 2020, and have gone on to not only announce but complete the reverse merger IPO of their target.

- 84 who have announced their target and are in the process of trying to complete their business combination.

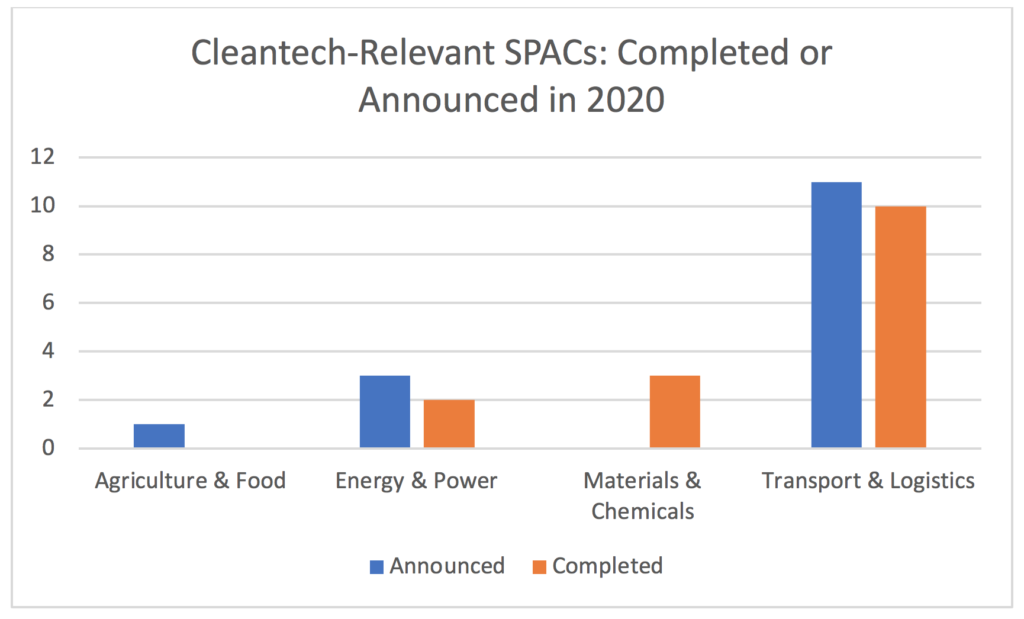

In 2020, we counted 30 transactions where a cleantech-relevant target was announced, 15 of whom went on to complete the transaction by year end.

Of the 15 SPACs who completed in 2020, their business combination including the listing of the new entity, they achieved an average enterprise value of approximately $2 billion and raised an average of $487 million in cash to fund future growth plans.

Of the 30, 21 relate to the future of Transportation & Logistics, with the strongest focus on some of the most capital-intensive parts of the electrification theme (electric vehicles, powertrains, batteries and charging solutions) and indeed LIDAR for autonomous vehicles.

Where now, what next in 2021?

We will provide a review of Q1 2021 in April, but a few thoughts for now…

The trend has not abated – at either end of the pipeline. Far from it.

Two more companies from our 30 above in 2020 who announced a deal with a SPAC have now completed their deal in 2021 and are now publicly trading – Advent, the fuel cell company and AppHarvest, the indoor farming company.

At least ten more SPACs have announced definitive merger agreements with cleantech-relevant targets during the first weeks of the year. The strong emphasis on electrification continues, and indeed our Global Cleantech 100 alumni are to the fore, led by Proterra (electric buses), EVGo and Volta (EV charging) and Li-Cycle (EV battery recycling).

As of this week, they were joined by the biggest EV-related SPAC yet, with Lucid Motor’s $24 billion pro-forma valuation, leaving it a staggering $4.4 billion of cash to take its luxury SUV to global markets.

A further 165 SPAC IPOs have already been priced in 2021, meaning there are now over 330 SPACs looking for their target, with their clocks ticking since the terms of their IPOs will mean they only have so long, typically two years.

What to look out for in 2021?

The SPAC in cleantech trend looks set to continue. If cleantech-relevant targets continue to provide 25%-33% of the targets of 2019+ SPACs, as they have done to date, then we might expect the total number of such companies who have listed via a SPAC or announced a deal to do so by year end, to even exceed 100.

We are expecting to see diversification from EVs into one of the many other globally relevant themes caught under our umbrella cleantech theme. More in Agriculture & Food seems a reasonable bet, given the strength of venture-generation in this field, combined with the pandemic laying bare how un-resilient and unsustainable the current food system is globally.

We also expect to see additional geographical diversity – SPACs targeting companies in Asia or Europe. January saw, for example, the pricing announcement of the European Sustainable Growth Acquisition Corp, led by former Cleantech Forum Europe keynote, Lars Thunell.

Performance of those who have completed these transactions specifically, alongside the market as a whole, given the growing number of voices warning of a major correction, will be an important signal as to how long this momentum persists, and how long the market has such strong appetite for not only loss-making companies, but in a number of cases, pre-revenue companies.

How to view this trend – positively or negatively?

For those of us who have been around this theme for 10+ years, there is certainly some degree of nervousness of the cleantech investment theme getting a bad name again, as it did in 2009-13, from investors’ over-exuberance and/or loose global monetary policy, which gives few investment options but equities.

But ultimately, we should embrace the ride ahead positively. Climate finance and sustainable investing are becoming terms in big finance’s lexicon. We can only be happy about that.

And it would seem entirely wrong to complain about a wall of new deep-pocketed money from fresh sources, finding our theme and buying into its three-decade growth story as we pursue the necessity of net zero by 2050, and the trillions that will entail to get there, after spending the best part of a decade of surviving on fumes and incumbent corporations (a group who were critical to progress made during the 2010s but a group who need competition for the overall health of the ecosystem and for the transformations ahead to accelerate faster, a point well-argued by Wal van Lierop in point 2 of his We Need An Operation Warp Speed To Battle Climate Change).

With the overall net zero mission hat on, even if investors in specific companies do not get the returns they expect, the market frontier will be changed by this SPAC wave, and our chances of decarbonizing by 2050 will have improved.

Consider how much capital is now behind electrification in SPACs. Add to that Tesla, NIO and what all the incumbents are doing, and politicians are saying.

Are we at the point where too many now have so much at stake, that electrification for much (not all) of future of transport is almost inevitable?