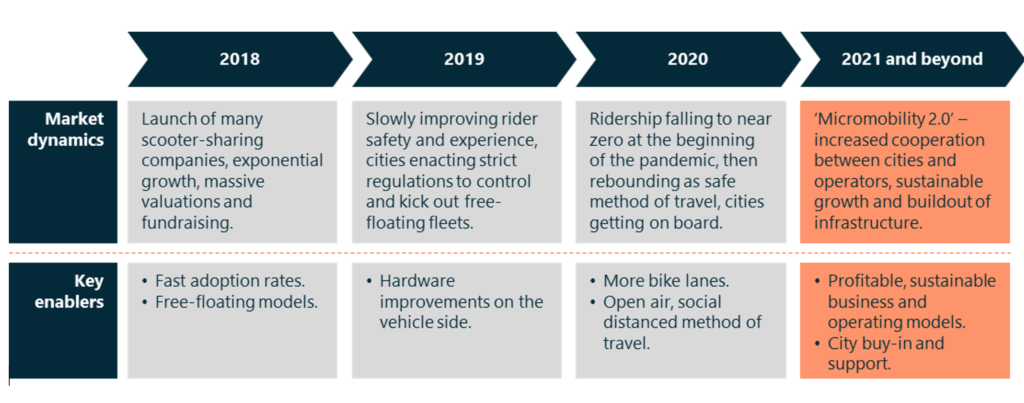

Bikes and scooters are nothing new. But combine them with the proliferation of smart phones, advanced mobility service platforms, and as-a-service business models and it’s clear to see how these purpose-built, lightweight vehicles designed for sharing are disrupting urban transportation.

Ever since Bird launched in 2018, quickly reaching over 10 million rides across 120 cities in 14 months while also achieving a $1 billion valuation in May of that year (becoming Silicon Valley’s fastest unicorn ever), the micromobility industry has witnessed explosive growth. Since the beginning of 2018, investors have poured over $3 billion into micromobility startups and numerous competitors have entered the fray.

However, the large number of free-floating scooters and electric bikes now showing up on city streets, for which few regulations exist, has created both safety and waste hazards. In addition, cracks in the micromobility business models are quickly starting to show. Free-floating bikes and scooters can be deployed quickly and in high numbers, but this extreme growth is also accompanied by high operating costs and costly, unsustainable charging and relocation strategies.

Shared electric scooters and bikes promise to reduce emissions and congestion in cities, but changes need to be made on both the city and operator side to realize this potential.

Impact of Covid

City support for micromobility is key to the growth of the market because ridership largely depends on safe and accessible infrastructure, which mostly come in the form of bike lanes. Covid-19 has proven that micromobility is an essential component of a safe and sustainable urban transportation system – cities are rewriting rules, developing supportive policies and allocating more public space to bikes and scooters. The crowded buses and subways of public transportation, and even ridesharing services, are being swapped for open-air and socially distanced modes of travel. Lime’s CEO has described the pandemic ultimately as a “tailwind” for shared scooters, following a 95% drop in ridership at the beginning of global shutdowns. The company just reached 200 million rides; interestingly, 100 million occurred in the last 13 months alone, after the first 100 million took 28 months.

However, most micromobility services suffer from unprofitable business models based on bad unit economics. The cost of maintaining each scooter is greater than the revenue generated. To fix this, operators such as Lime and Bird have focused on the scooters themselves, rolling out multiple generations of scooters which last longer, have more battery capacity and are resistant to theft and damage. While this is one part of the equation, charging and relocation still represent around 50% of the operating costs of electric scooters, and safety hazards—including free-floating, dockless scooters and bikes being left in the public’s right of way—are still a concern. Innovative business models and infrastructure, such as new charging and docking models, can help solve this problem and make micromobility work for both the cities and micromobility operators.

Attractiveness

There are currently three dominant models for scooter charging and relocating:

- Gig workers: Contract workers, sometimes known as “juicers,”pick up scooters, transport to their homes (or other place with access to outlets) and get paid for each scooter charged.

- Third-party logistics providers: Micromobility operators contract with third-party companies to collect and recharge scooter fleets.

- Warehouse workers: Operators use in-house workers to pick up scooters and transport them back to company warehouses for recharging.

While all of these have enabled micromobility companies to scale rapidly, these methods are costly, have a huge environmental impact and can severely damage scooters and bikes. Micromobility operators pay $5-$8 per scooter using the gig worker model, and relocation and charging can account for about 50% of operating expenses. In addition, gig workers are incentivized to charge as many scooters as possible, often throwing dozens of scooters into the back of fossil fuel-powered trucks for transport; this damages the scooters and reduces the overall GHG emissions savings from micromobility. New solutions are rewriting this part of the micromobility business model – either improving existing strategies or developing new ones entirely.

Business Models

Distributed container-based charging

Perch Mobility has developed a distributed network of retrofitted shipping containers equipped with charging equipment to provide safe and secure places to charge vehicles. The containers maintain the gig and warehouse worker models but mitigate some of the negative aspects of the models, including long-distance transport. The shipping containers operate as self-sustaining IoT devices and can be used by gig workers, third-party logistics providers or in-house warehouse workers on an hourly or subscription basis. The containers reduce scooter downtime, enabling charging at any time of day (rather than just at night), and reduce transport distances between pick-up and charging locations.

Charging and docking hubs

Swiftmile is a San Francisco-based developer of a docking and charging system for electric scooters and bikes. The company provides charging ‘hubs’ in high-traffic areas and uses ad-supported charging stations to eliminate any capital expenditure to cities. The semi-dockless model includes the charging/docking stations where it makes sense but allows users to end their ride without a dock to increase flexibility. In July, Swiftmile raised a $5 million Series A round from Thayer Ventures, Alumni Ventures and Verizon Ventures.

Knot Scooters is a France-based provider of docking, charging and locking infrastructure for electric scooters. The company’s hardware-as-a-service offering can host different mobility service providers, accommodating any solution with a proprietary backend application. Kuhmute offer a flexible docking solution as a hybrid between docked and dockless rental. The multimodal charging hub utilizes vehicle adapters to allow scooters and bicycles to charge from the same plugs. Kuhmute’s model uses incentives (waving the unlock fee) to boost the usage rate of hubs. This is key for the economics of hub-based charging, as the return on investment increases with rider usage.

Competition

The micromobility charging and docking market is still young and highly fragmented, with many newcomers and space for new players. Now, most players are early stage, and a range of business models are being tested. Relationships with cities are key. Cities will likely be hesitant to allow multiple infrastructure providers to build out charging hubs and will instead choose those aligning most closely with the city’s goals, municipal regulations and transportation system. In this way, competition will also be geographically-based and influenced by local micromobility operators. At least in the beginning, infrastructure providers will be competing for relationships with smaller, local operators, as larger players will take a wait-and-see approach and develop proprietary solutions if the economics and regulations prompt them to do so.

Keep an Eye on…

This space is largely regulation-driven, so we can expect to see the most innovation, as well as adoption of new charging and docking solutions, in cities with tighter regulations on micromobility. For example, Washington D.C. recently approved a new regulation on scooters that requires operators to provide a way for the devices to be locked to racks or poles.